To be stagnant in this business is to punch your departure ticket from making a living making pictures. If you are doing things the same way you did even five years ago, you’re probably on the downhill side of your career path – unless you’re uniquely talented and have made yourself known to a well paying, admiring market.

Of the many ways to continue to evolve is the core of what we do: Make and select photographs. These are two distinct acts. Your approach to making photographs may have changed over time but if you’re still choosing the same types of photographs that you made years ago, then your growth in the making phase will be invisible.

Here are a couple things you can do to see if there is evolution in both aspects.

Look at the photographs you chose as your best a number of years ago – five or 10 or 20 years – and compare them to your current top tier of work. This taps into your making eye. Evaluate what has changed and what has stayed the same. You may notice that your seeing of light has improved, your compositions have become more dimensional, the range in the types of photographs you’re making is far greater now compared to then, when you pretty much made the same kind of photograph regardless of what was in front of you. Or maybe things haven’t changed? Ouch.

A second step is to go back into raw takes from years ago and see if you would choose photographs now that you didn’t then. This taps into your selection eye to see if it has grown. If you would choose only the same pictures now, that’s not good. Almost all of us will have made dimensional pictures in the past that we didn’t choose then because they were not in the vein of what we valued at the time. Some of the past photos inevitably were harbingers, you made them in response to a setting in a way that set new parameters for your making eye but your choosing eye said, “Uh, no thanks.”

You can also engage someone like me to review your work then and now. When I work with people I always ask them to send me a deeper selection of photos than would tend to. If you’ve created a hierarchy in your archive of best, second best, third best … then I ask people to send at least down to the third best level. There are always surprises that reveal a more complex you in those photographs. That’s among the things I’ve found after looking at hundreds of photographers’ work like this.

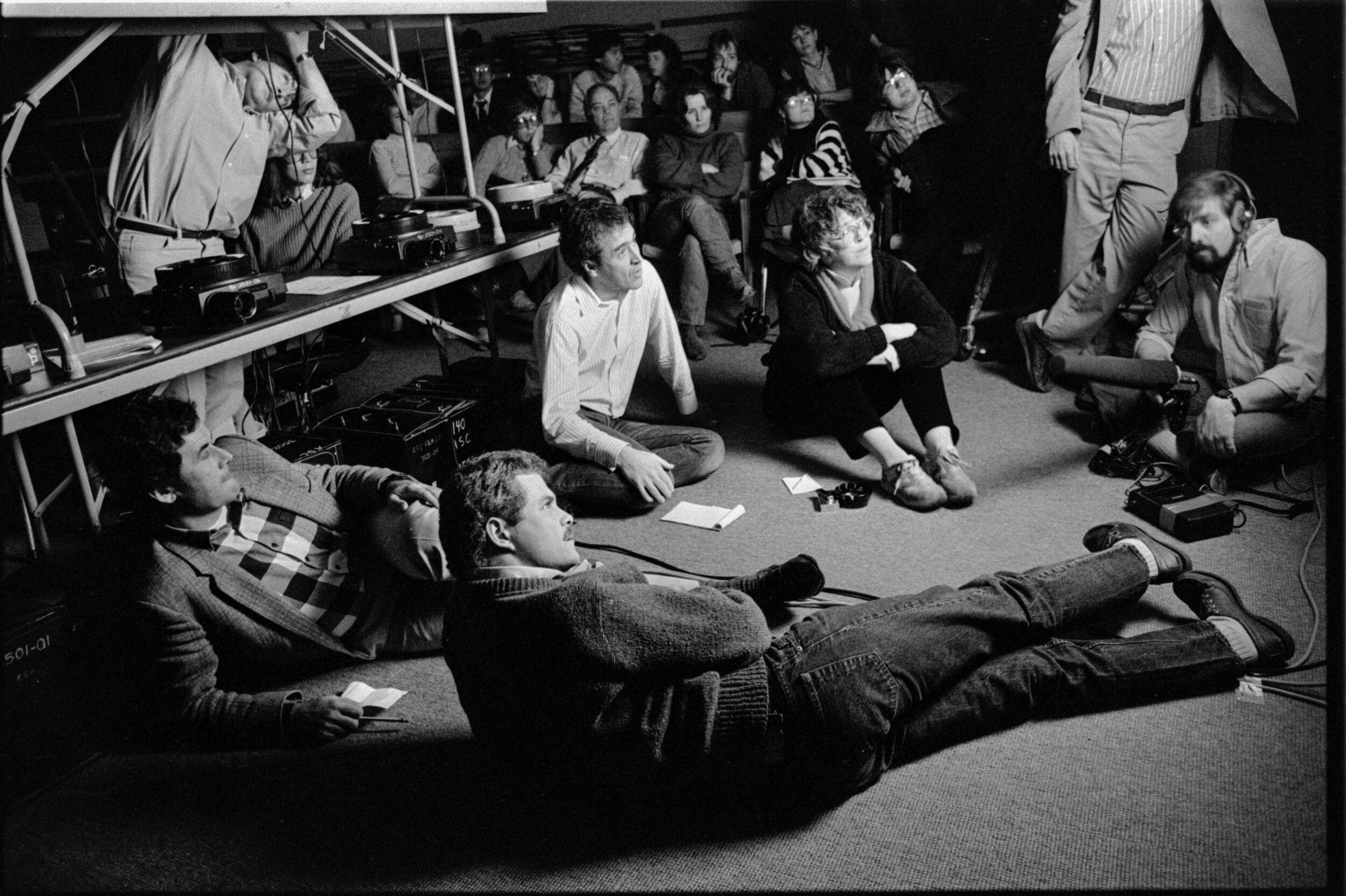

To test this notion on myself, I went back to my own archive to a set of pictures I made while in graduate school at the University of Missouri. It was 1986, the last year that Pictures of the Year was judged with prints. I volunteered to photograph the judging just to be able to hear the judges’ every word and learned so much.

One takeaway from my exercise is that I tended to choose simpler, self contained photographs back then and left unchosen photos that were more complex, those that required and rewarded spending more time with and used the full depth/dimensions of the frame.

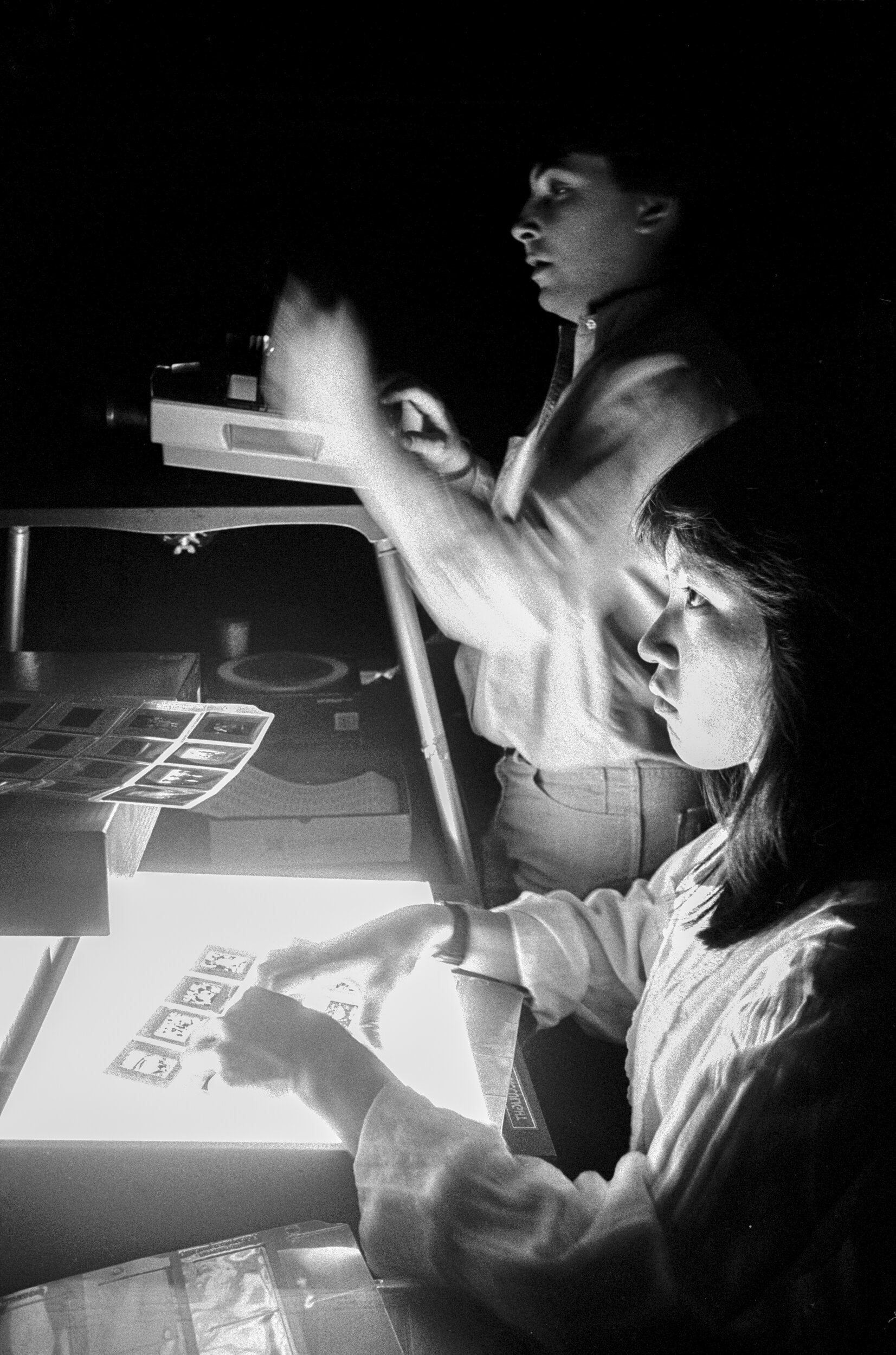

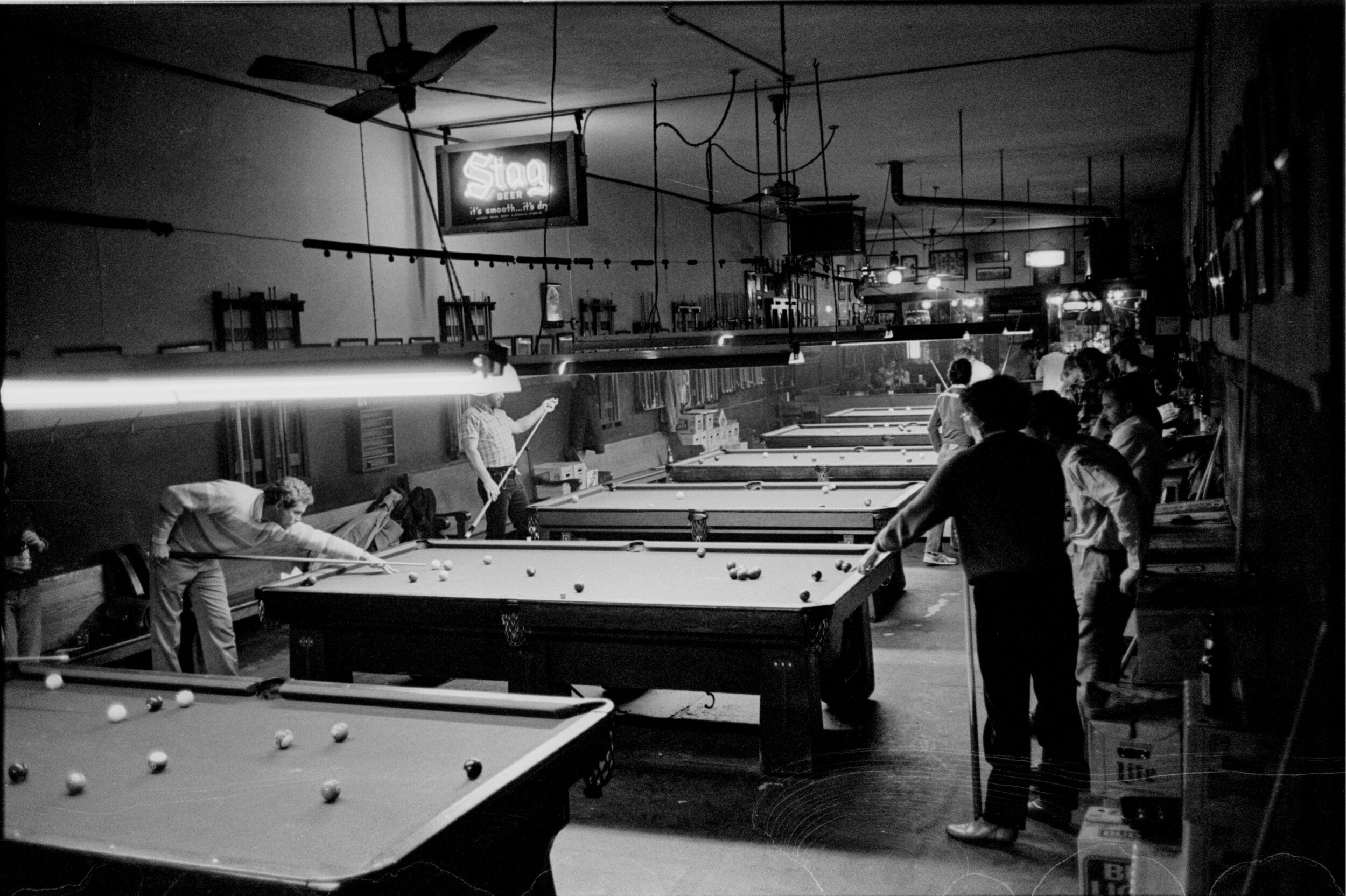

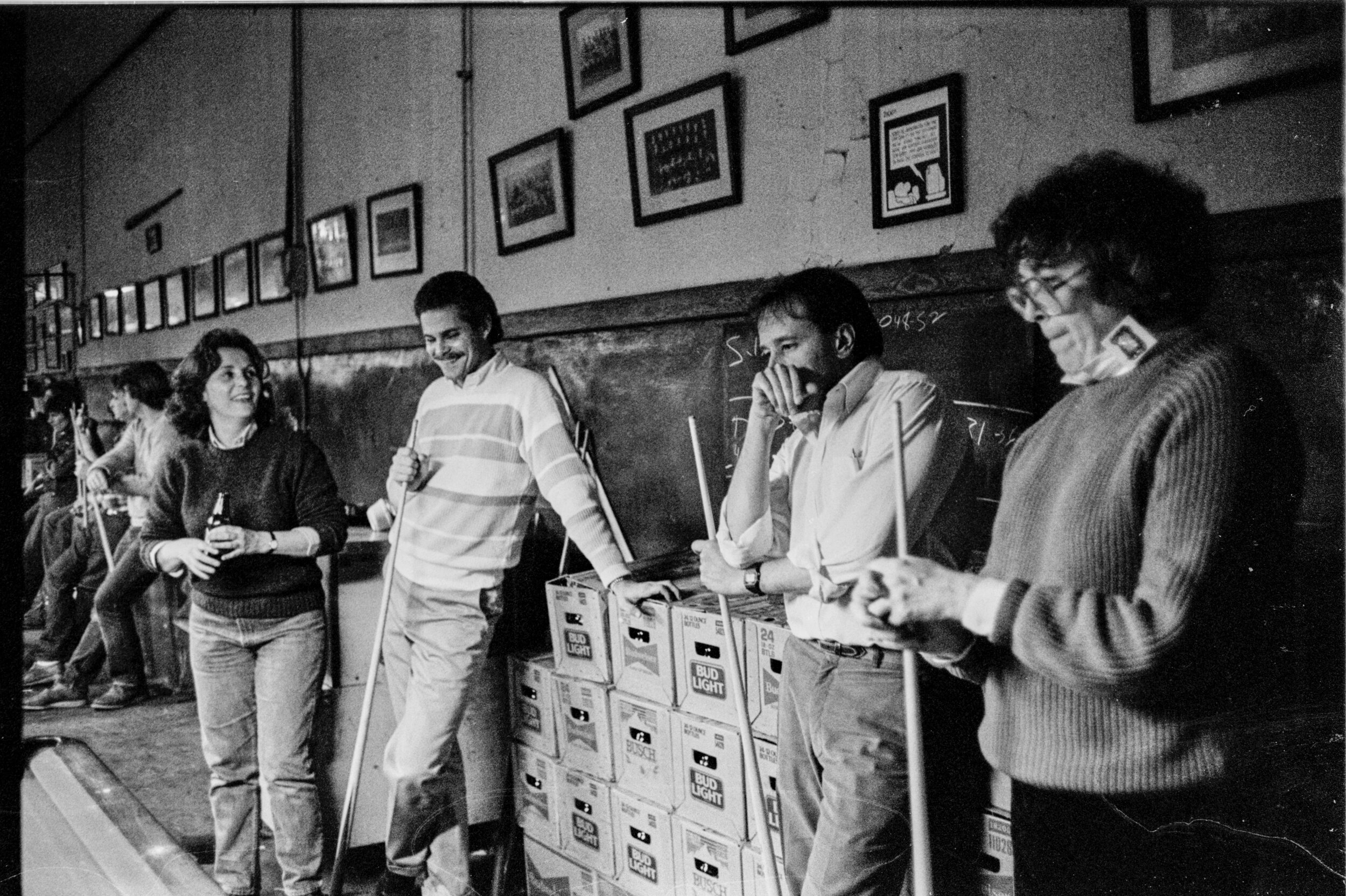

Here is one gallery of four photos that I did choose back then and another gallery of photos that I resurrected from the contact sheets. And one photo of me while making photos.

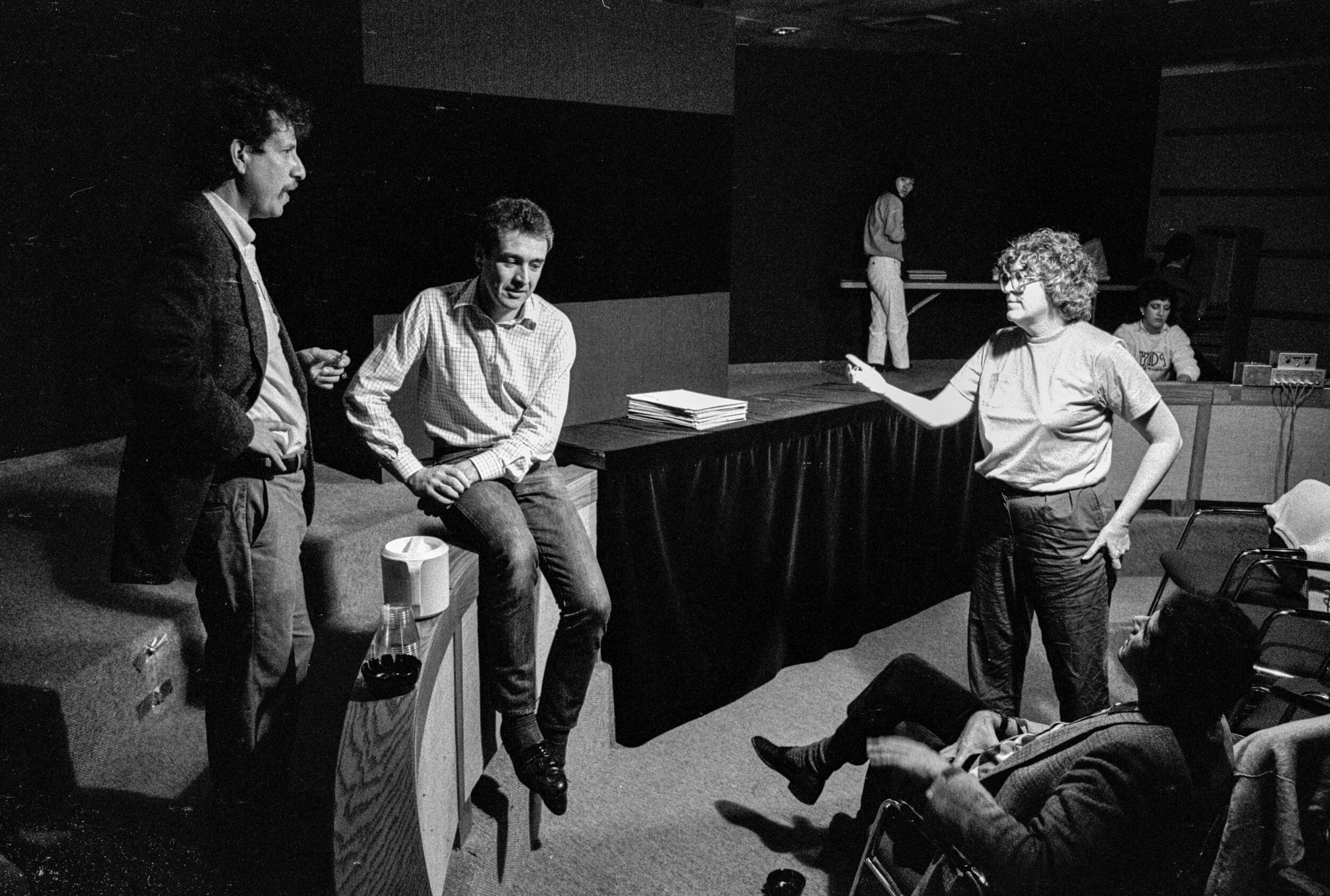

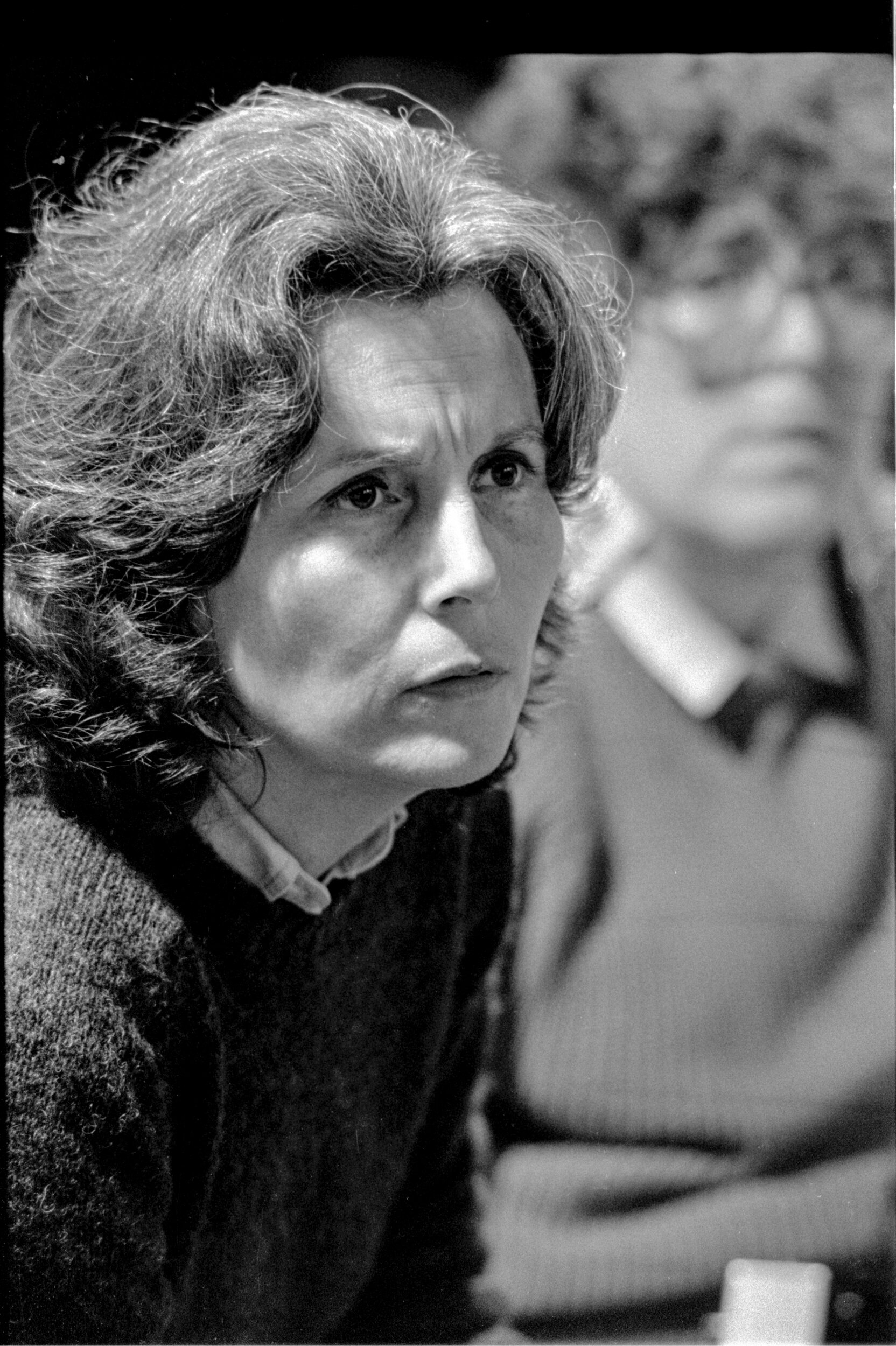

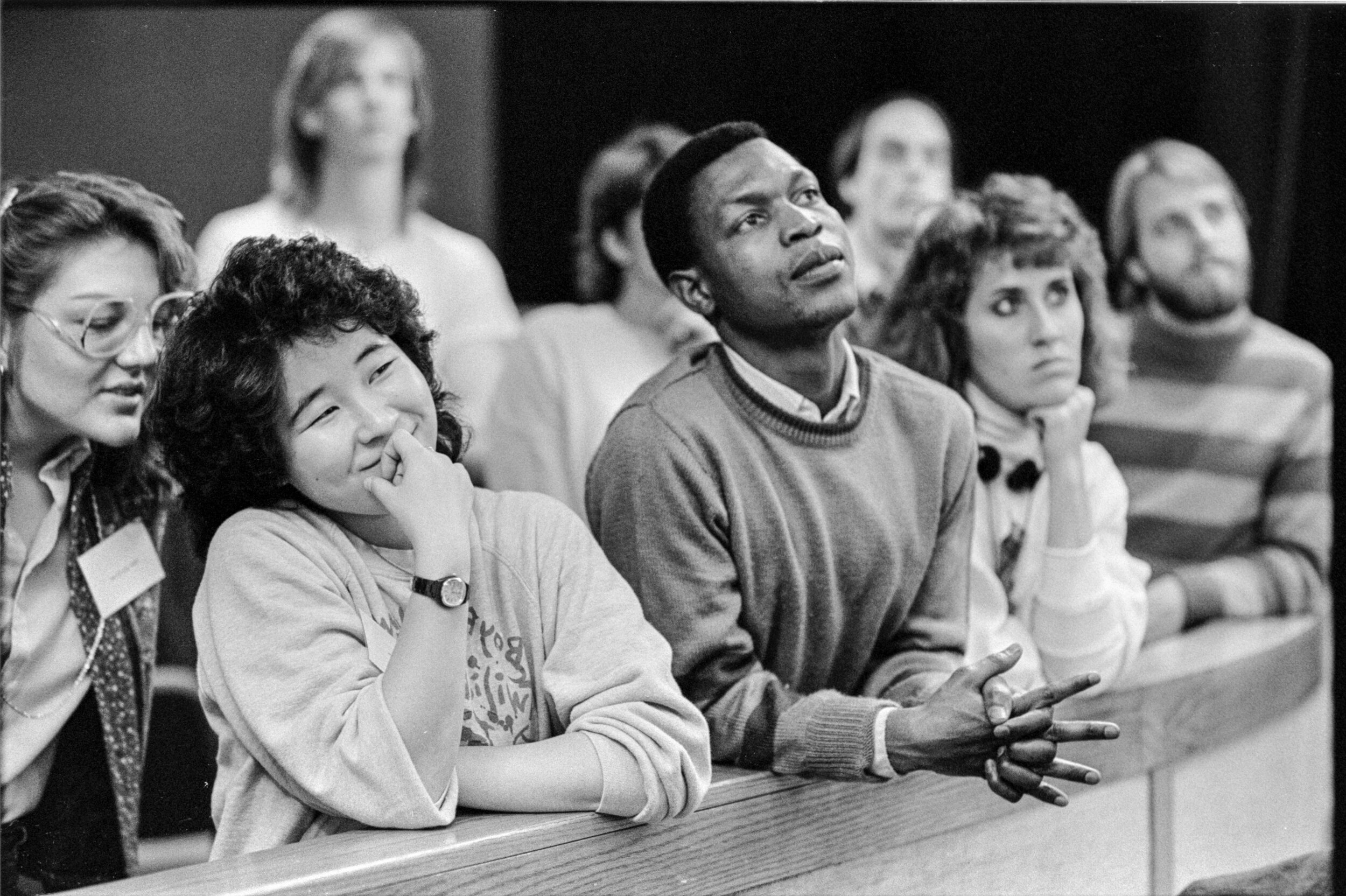

Judges that year were Larry Price, Karen Mullarkey, MC Marden, Bruno Barbey and Peter Howe. In the first photo you may recognize some of the students holding prints, including Pat Davison, second from left, and Dave Eulitt, fourth from left, with hair.

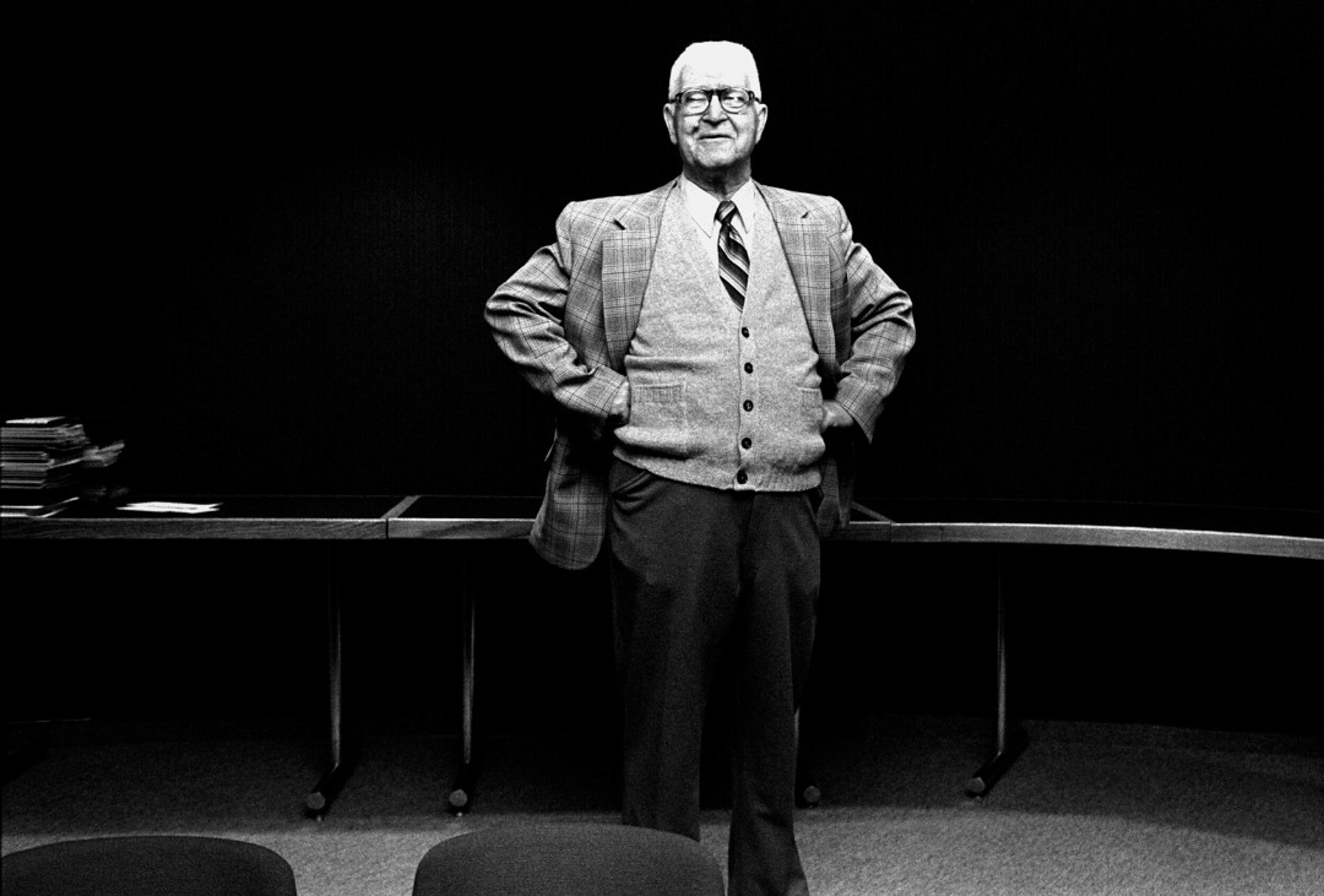

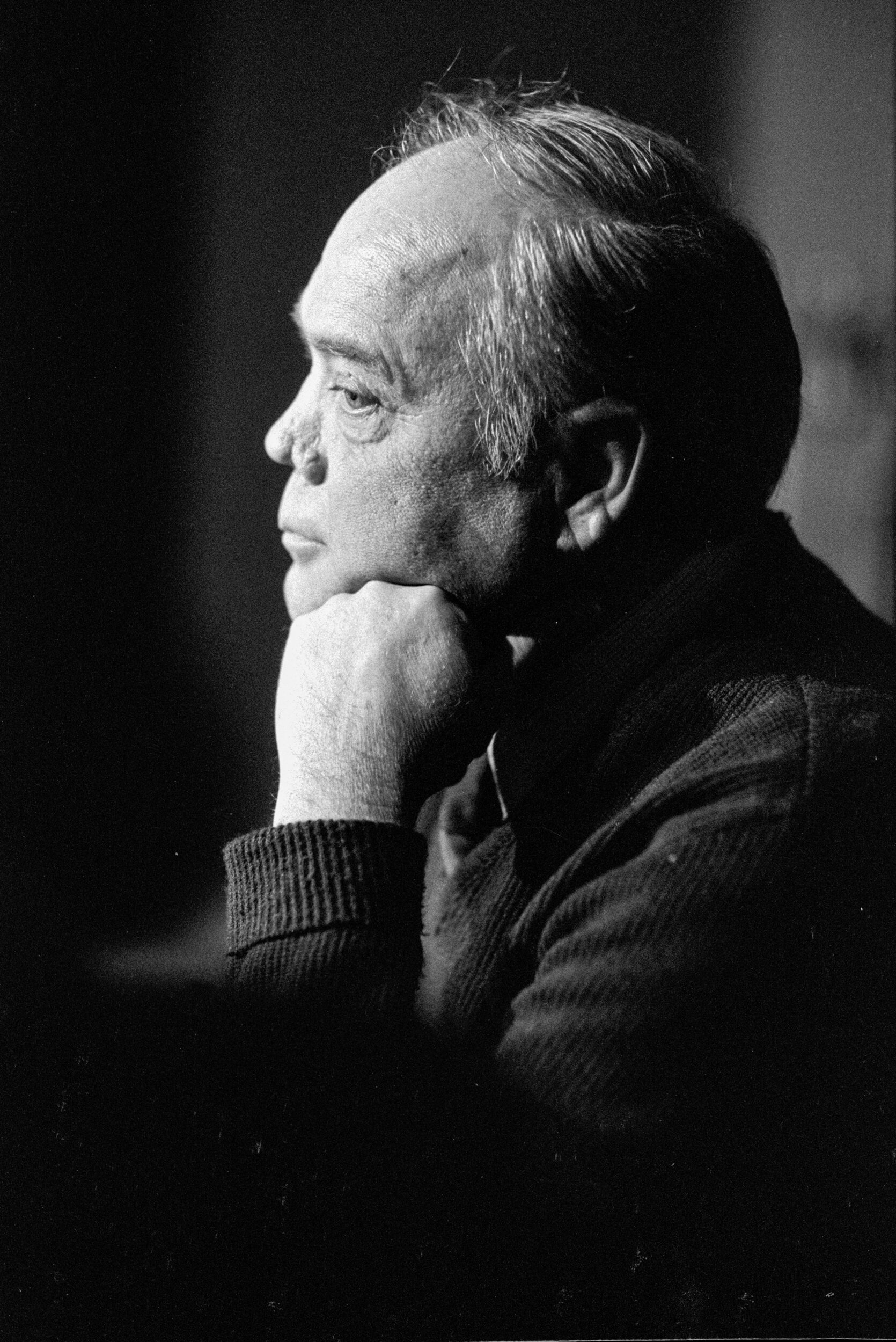

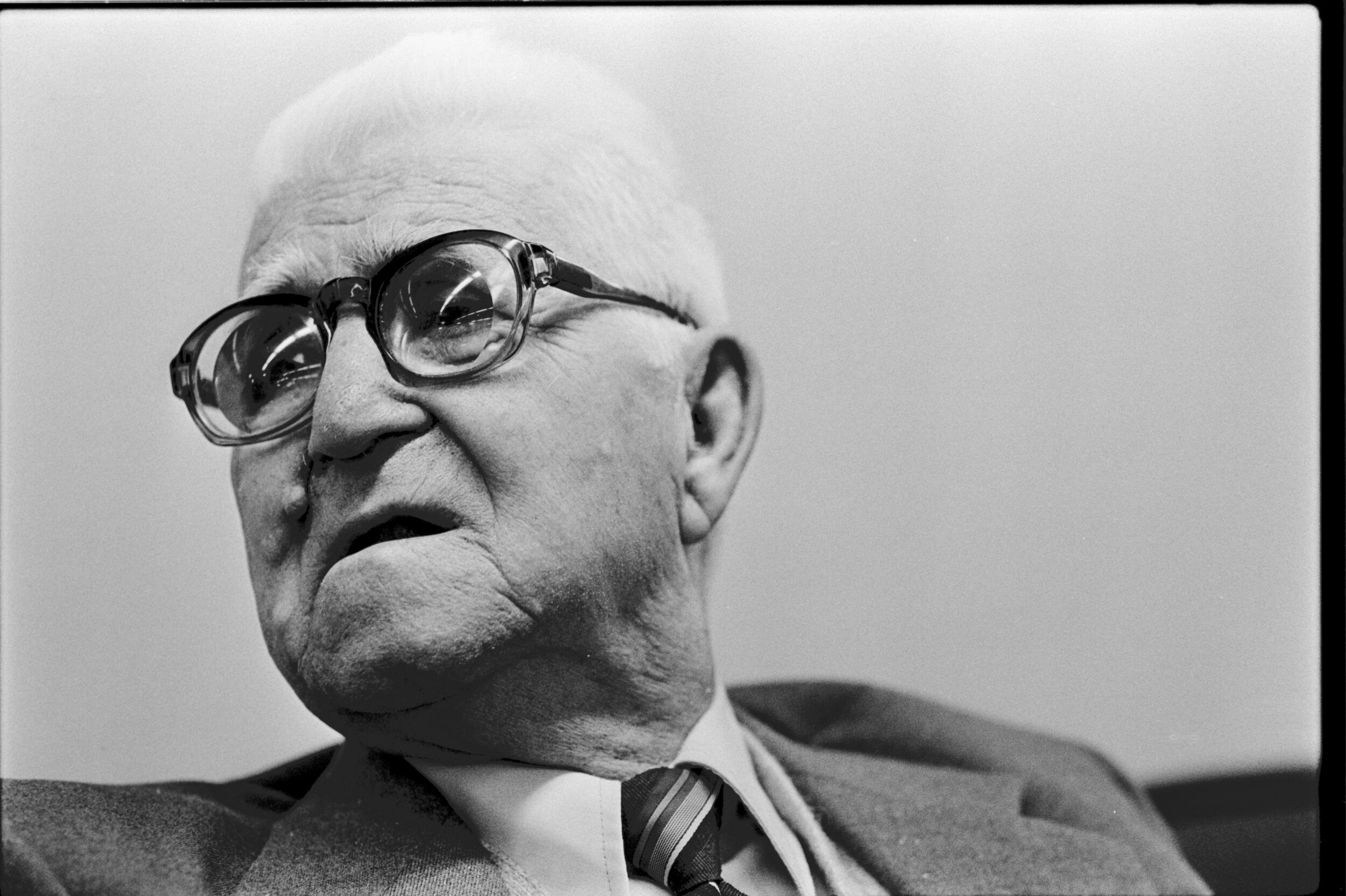

That’s Cliff Edom holding his hands on his hips, founder of the Missouri Photojournalism program and Workshop. What an inspiration he was. And that’s Otis Imboden in the vertical portrait. He was NASA’s first photographer and was at National Geographic at the time.

Mizzou grads will recognize Booche’s pool hall in the second gallery. One of the benefits at Mizzou was that we as students got to be up close with the prints, in one of these photos Mary Schulte is in the middle and Chris Horn, the two classmates I remember.

Yes, that’s a Canon F1 and I used to have a little more hair..