Making pictures that trigger memories and tell stories long after the immediacy of the experience fades is one of the gifts that photography can offer – if we take advantage of the potential.

There are many ways you can increase the longevity and relevance of your pictures, whether you make pictures for a living or not. One of those ways is to make pictures of a layer of life on the planet in a thoughtful and considered way over an extended period of time. This layer can be of your own life, of your children, of the color purple wherever you see it – there are no limits to the possibilities.

What drives people to pursue a particular subject is often personal. They can be heavy or fun or pursued solely to capture the passage of time. They’re nearly always done not for remuneration but for personal growth. The more anyone sets out to do with their body of work, the more growth there is.

Some examples come to mind: Vince Musi and Callie Shell made sure they made at least one picture of their son every day for several years, starting with his birth. Bill Luster photographed hats wherever he saw interesting ones and makes sure he photographs every governor of Kentucky. Gerd Ludwig has been photographing Russia for more than two decades. Quang-Tuan Luong has photographed every U.S. National Park.

The notion of creating bodies of work that become more relevant with time came to focus for me when I was the lead picture editor for the White House Photo Office. As a picture editor at National Geographic magazine I had learned a lot about how to craft huge narratives of sweeping topics with photographers and the White House experience added an historical imperative to the work.

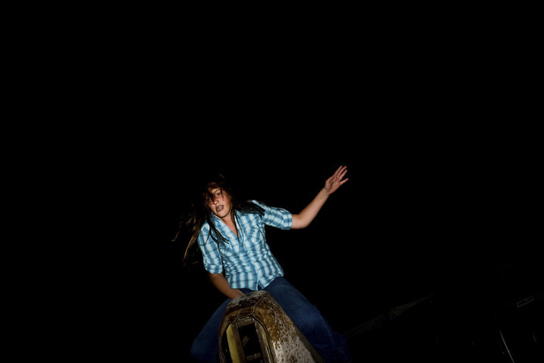

Those and many other experiences came to play recently while working with Matt Slaby on his personal project about the American West. It’s a sweeping body of work that is very personal to Matt, who grew up and still lives in Denver. Matt is part of the innovative photographic cooperative Luceo Images. He holds a law degree and makes his life from photography.

Matt and I have completed the seemingly daunting but actually pleasurable task of editing his Western work to date into a group of pictures he’ll submit to World Press Photo’s Joop Swart Masterclass for photographers who are 30 or younger.

Here are three pictures with a common aspect from his story:

I asked Matt a few questions about how and why he approaches such a sweeping topic. Here is some of what he said:

MD: How did you define the scope of the project?

Matt: Initially, the specific focus was to complete smaller bodies of work for different purposes. The larger arc of the project only started to take form when I realized that each assignment or small essay that I took on was channeling in common archetypes and ideas. Once I found that thread, I've been able to keep it in the back of my mind and add photographs as they present themselves in my ordinary shooting.

MD: How long will it take?

Matt: It's hard to put an end point on something like this, but I think that the goal is to communicate something that is honest, thoughtful, and true to my own perspective. Could be another year, could be another decade.

MD: Why have you used different photographic approaches and created several subsets of pictures?

Matt: “This is a matter of aesthetics and personal choice. I know there's a lot of pressure to make a body of work stylistically streamlined but I'm a bit more drawn toward things that are eclectic, spontaneous and punctuated. To me, the strobe-spot portraits and the car window material serve as punctuation, something to anchor sections of the work. To me, it feels like you're walking though a tunnel with a flashlight and you get to take in your world one quick item at a time, sorting significant items from the insignificant as the light beam passes along the ground.”

MD: Why do long term projects?

Matt: “Long-term projects are really the only way for photographers to move their craft forward, especially photographers who tend toward the editorial side. It's hard to weave a visual thread that is true if you've only got a day to do it and I think that it's even harder to really get to know a subject without spending some time inside of it, experimenting, thinking, shooting, reshooting. The most valuable lesson from looking at this initial chunk of work has been understanding the kinds of photographs that I am drawn to and trying to figure out why I am missing other images that have likely presented themselves but I've ignored. By doing that kind of an inventory, it's possible to refocus the hunt a bit and to start looking for photographs that fill in those gaps. In that regard, it changes the way you approach any shoot because you're looking for things that you might be predisposed to avoid or ignore. That invariably has to change your person as well as your shooting.”

There’s a lot to learn from how Matt thinks about and makes pictures.

So how can anyone begin to work on their own personal project? I’d suggest starting close to home. Begin an essay about your own life. Think about the layers of your life and produce pictures about them. As whole, you’ll produce a time capsule of your life that travels forward with you.

Here’s a framework that creates a simple but dimensional interlace of who you are:

1. My stuff. Make pictures of where you live, what you drive, your favorite things. Create subsets: An archive of your possessions, down to the inside of your refrigerator; what you eat for a month; the view out of your window. Make photos close and far away. This introduces object-based photography to your time capsule.

2. My family. Make photographs of your relatives that say something about what you think of them. Include settings, reasons for getting together and what people were wearing as an equal layer of the image making. This introduces people and places to the body of work.

3. My time. Make pictures of how you spend your time outside of home and family – meals out with friends, hobbies, your work place, your vacations. This introduces activities connected to settings.

Imagine if 1,000 people did this, or a million people. The story it would tell of life on the planet would be phenomenal today and significant forever. What a gift.

Writing this piece encouraged me to start my own personal project, one about bicycles.